(This is the second part of our coverage of new emergency department wait time data. You can read the first part here.)

Ontario's health minister said Wednesday that a lack of government spending isn't the problem causing emergency department wait times to reach a historic high.

"This is not a money, investment conversation or challenge," said Sylvia Jones at a media conference in Mississauga.

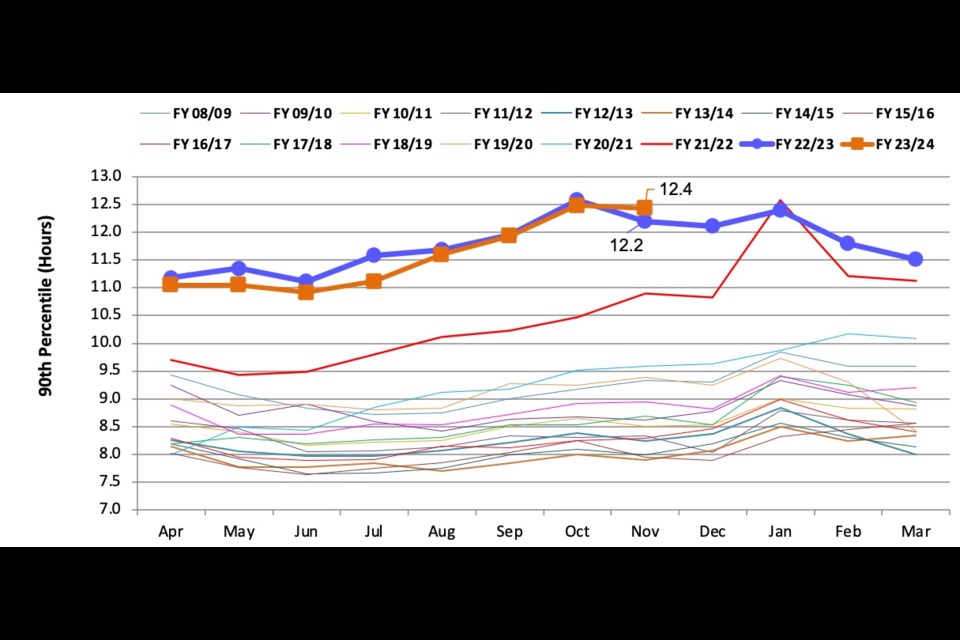

She'd been asked about provincial government data obtained by and reported on by The Trillium that show wait times in Ontario hospitals over the past two years have far exceeded the pre-pandemic norm, driven by an increase in the time patients who are admitted to the hospital must wait in the emergency department before they get an in-patient bed.

The data show that 10 per cent of emergency patients admitted to hospital wait more than 48 hours from when they walk in the door to when they're in an in-patient bed.

Three emergency physicians and the head of the Ontario Hospital Association spoke with The Trillium about the problem, and none said that an influx of cash to hospitals could swiftly fix it. Instead, they spoke about structural changes and investments — which would be extremely costly over the long term — that must be made, as well as some shorter-term actions the Ontario government could take.

Jones' diagnosis of the problem is in line with that of the experts and backed by her government's data — there are not enough available in-patient beds. She said she'd like to see patients moved into an in-patient bed as soon as the decision to admit them is made. For those 90th percentile patients who wait 50 hours in the ED before they are admitted, that would eliminate about 40 hours.

But being able to do that would require, according to emergency physician Alan Drummond, bringing hospitals' occupancy down to the safe level of 85 per cent from the 100-per cent-plus that is the norm today.

"If there was anything that could be done that was going to have a significant impact, it would be to increase the number of staffed hospital beds, which is not a cheap proposition," he said, estimating the annual cost per bed at $300,000 to $400,000 a year.

Another emergency physician, Raghu Venugopal, agreed, calling on the province to "radically and historically" increase the number of staffed hospital beds in the province.

But both said that's not the end of it.

Getting down to safe levels of occupancy would also require a massive investment in human resources and infrastructure outside of hospitals, according to all of the experts who spoke with The Trillium, and Jones herself.

Jones said Wednesday that 3,000 additional hospital beds are in the province's pipeline to be built. Her government is also aiming to build 30,000 additional long-term care beds by 2028.

"They're not building them fast enough," said Drummond. "That much is for sure."

Drummond also warned that the new beds will have to be used properly — for patients with acute health-care needs — rather than allowing the continued expansion of patients in hospitals who really don't need to be in hospitals because they lack sufficient family support, adequate home care, or a bed in a long-term care home.

The issue of alternate-level-of-care (ALC) patients — those who no longer need to be in hospital but lack a safe place to be discharged to — is well known and was cited by each of the experts, and by Jones.

Anthony Dale, president and CEO of the Ontario Hospital Association, blamed the "lack of adequate capacity outside the hospital setting" as the primary problem, citing the persistently high numbers of ALC patients, but also said the province needs to look further to expansion of acute-care and post-acute care beds, while giving it credit for continuing to fund staffed 3,000 beds that came online as an emergency measure during the pandemic.

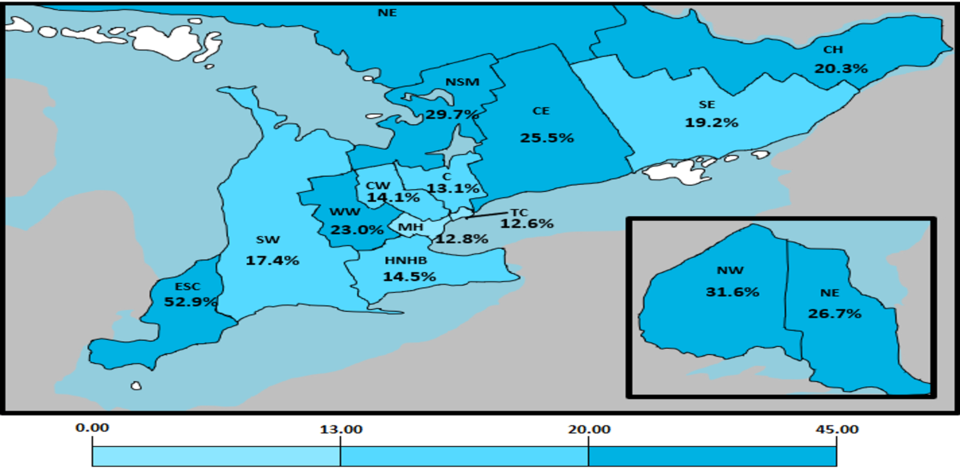

ALC rates are included in the report on the province's emergency departments obtained by The Trillium: in November, all regions were above the 10-per cent benchmark for the share of hospital beds occupied by ALC patients, with the Erie-St. Claire sub-region the highest at 52.9 per cent.

Alternate-level-of-care rate by health sub-region / Ontario Health

Adil Shamji, a Liberal MPP and a Toronto emergency physician, said that's far higher than the rates were a year ago and said it means the government's controversial policy to move some ALC patients into long-term care beds against their will, with the threat of fines, is not working.

Instead, he said, the problem is the lack of health-care workers in the province who could keep those patients out of hospitals, living in the community or in long-term care.

"It is a testament to the fact that the real reason that we're not able to clear beds and ensure that people get care in the right place is a lack of attention to health-care worker retention. And for as long as they don't do that, we will continue to see these elevated and increasing ALC rates in our province."

Venugopal agreed and called on the government to improve the work environment for non-physician health-care workers, starting by abandoning its appeal of the court decision and striking down its wage-restraint legislation known as Bill 124 as a sign of goodwill toward the workers.

For her part, Jones emphasized that her government is "making sure that we have sufficient health human resources out in our communities to serve our communities," but her approach has been focused on bringing new workers into the province through immigration and ramping up education programs, rather than retention.

Drummond said the loss of experienced nurses is a direct challenge to hospital emergency departments: when they're replaced by a temporary worker assigned by a staffing agency or someone fresh out of school, wait times tend to increase because of that loss of skill.

The staffing issue is particularly acute in the home and community care sector, where organizations are pleading with the government for the money to recruit and retain workers in the coming budget. The government is also reorganizing the home care system in a way that some advocates are warning could destabilize it.

There are similar concerns about the government's move to allow private, for-profit clinics to perform ambulatory surgeries: the primary concern expressed by its opponents, including all three opposition parties at Queen's Park, is it will drain staff away from the rest of the health-care system.

“This move threatens to exacerbate our health-care crisis, worsen our staffing issues, subject patients to predatory practices like upselling, all while the government rewards its friends and sticks its head in the sand to the fundamental issues that are undermining health-care," said Shamji in a statement Tuesday. “Minister Jones and Premier Ford need to implement a comprehensive and material health-care worker retention strategy immediately if we are ever to see universal improvement in Ontario’s health-care system under their leadership.”

Drummond echoed concerns about the lack of will at the political level to address the problem with a comprehensive plan.

Drummond said the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians met with the country's health ministers last fall in Charlottetown, where it proposed working on a collaborative approach between political leadership, health-care providers in hospitals, home care and long-term care, to plan a way forward.

"We were quite willing to take the blame away from government — share the blame — get the whole thing moving with new ideas," he said. "And nothing. Zero."

In fact, he added, some of the reaction was quite dismissive.

There has been some progress, and some things can be done more quickly than labour expansion of infrastructural and human capital, according to Venugopal.

For instance, some patients can be safely discharged from the hospital sooner if they are assured to get follow-up care immediately in hospital clinics specializing in certain diseases. Some hospitals are establishing those kinds of clinics, and it's helping, but can't help the sickest patients, he added.

One thing that isn't causing the problem, according to all of the emergency physicians who spoke with The Trillium, is low-acuity patients flooding the emergency departments, which is often blamed. The data shows, conversely, that overall ED volumes are in line with previous years despite a population increase.

Drummond said that suggests that some people are staying away from emergency departments.

"And that has been our fear all along," he said.

He believes Canadians, "a pretty good lot," are aware that emergency departments are overburdened and don't want to add to that.

"And part of it is because they probably don't want to get COVID or influenza," he added. "And the third thing is that everybody knows that it's gonna be a miserable goddamn experience, that you're gonna be waiting for 12 hours. And people avoid that scenario, and there's limited access to primary care alternatives."

That means that when people they do come in, they tend to be sicker.

The consequences of overcrowded emergency departments for very sick people are clear, according to Drummond.

"When a young mother of three dies in a (Nova Scotia) hospital because of an eight-hour wait, and that's all over the national media. But when somebody's grandma, who has been waiting three days for a hospital bed, dies prematurely as a result of inadequate treatment, that doesn't get publicized. And yet, that's a daily occurrence in our emergency department," he said. "Part of the problem is government's failure to address the issue of bed availability, and the second part of it is just this increasing complexity of our aging population."