Ontarians who can't afford homes are taking drastic measures, trying everything from shipping containers to senior roommates to living in their van.

Some have even moved to Alberta.

Canada's largest province is facing a "brain drain" to other provinces due to its inability to build housing, according to economist and housing expert Mike Moffatt, the senior director of the Smart Prosperity Institute.

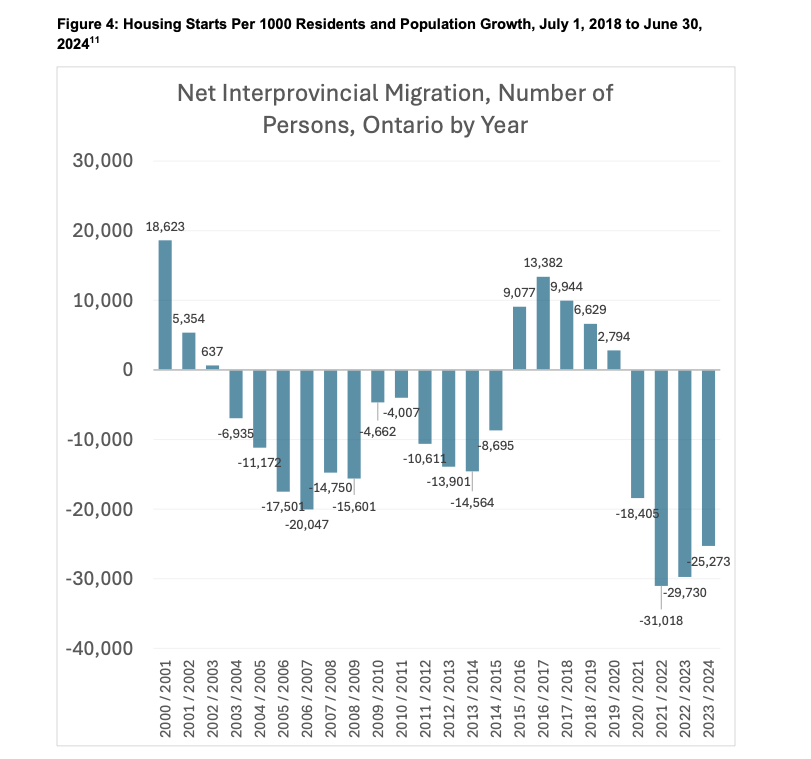

Over the last four years, over 100,000 more people have moved out of Ontario than from other provinces to Ontario, Moffatt laid out in a new report.

About a third of those ex-Ontarians have gone to Alberta, another third have gone to the Atlantic provinces, and the rest have spread out elsewhere in Canada, Moffatt said.

Some of those interprovincial migrants are seniors downsizing. Many are people in their mid-to-late 20s who have looked at the housing market and said no thanks, Moffatt said.

"The brain drain is young university graduates who are taking their first job. They're quite mobile, they have a lot of options," he said.

When they look at their wages and home prices, "the GTA just doesn't look that attractive to them when they can move out to Calgary or Edmonton or Halifax and get a lot more for their money."

Ontario falling behind Canada on homebuilding

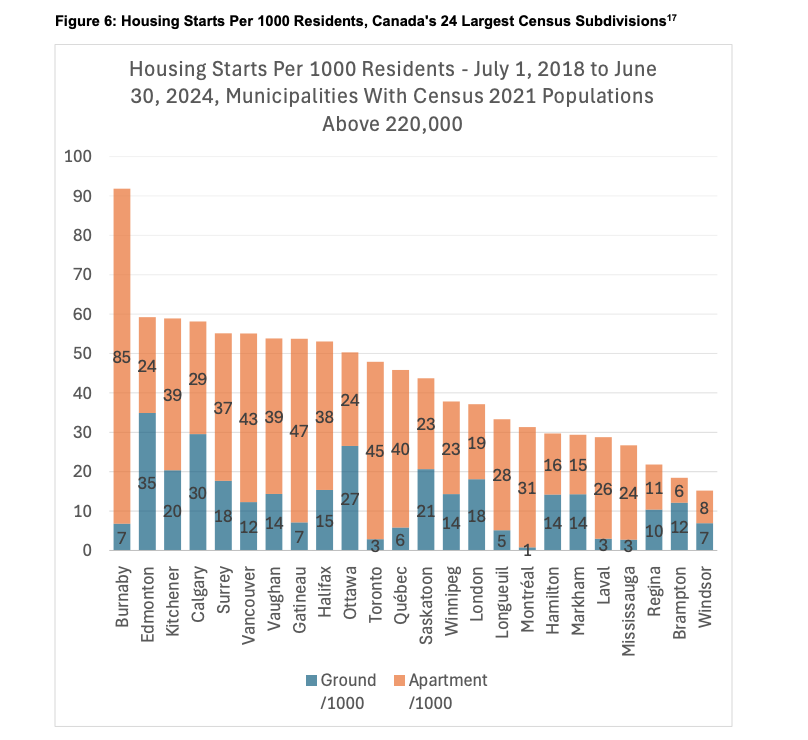

Moffatt's report ranks Canada's 100 biggest cities and towns on their housing starts per capita over the past six years.

Just three Ontario cities — Pickering, Oakville, and Kitchener — were in the top 20, while 13 of the bottom 20 are all in Ontario.

From January to October, 13,000 fewer new homes began construction in Ontario than the same period last year, while the rest of Canada started 14,000 more homes, the report notes, based on Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) data.

British Columbia has faced many of the same housing problems as Ontario. But the western province is making more headway, Moffatt said, largely by up-zoning to allow for more density, which Premier Doug Ford has been reticent to do.

Burnaby, near Vancouver, had by far the highest number of housing starts per person of cities above 220,000 people — largely led by apartment buildings, Moffatt found.

B.C. also tends to have lower development charges, though Moffatt noted they're going up, which could slow the province's progress.

Ontario cities could also learn from Edmonton, which has implemented automated building permitting, Moffatt said. That allows builders to get same-day approvals, as opposed to Toronto, where it can take years, he said.

Toronto is 15th overall in per-capita apartment unit starts. The city has made it easier to build highrises, Moffatt said.

"The challenge for the city is basically building anything else, and particularly building anything that is suitable for a family with kids," he said.

Moffatt noted that several of the Ontario mayors who have asked the province to let them use the notwithstanding clause to clear homeless encampments oversee cities where not much building is happening.

Signatories Brampton, St. Catharines, Windsor and Sudbury are all in the bottom 20, he said.

"I think city councils need to look at themselves in the mirror and ask, 'Are we doing enough to create housing?'" Moffatt said.

Government funding vs. outright intervention

In response to the housing crunch, the NDP has pitched "Homes Ontario," a new provincial agency that would build affordable housing. The party has released few details about the plan.

"We know that we want to build a large number of homes, and we're going to get the government back in the business of building homes — truly, deeply, permanently affordable homes," NDP Leader Marit Stiles said.

There's room for the government in homebuilding, Moffatt said.

"The market does not build and can't build deeply affordable housing. The math doesn't work (with) land costs and so on," he said.

Housing Minister Paul Calandra downplayed the brain drain woes. Ontario's economy is "on fire," he said, noting that Ontario added 800,000 new residents last year.

But he said he worried about young people still not being able to afford homes.

"Many people in this province have the benefit of a home because of policies that allow homes to be built faster and less costly. And now, all of a sudden, that has changed," he said.

Calandra noted that Ontario saw "some of the highest levels of shovels in the ground that we've ever had" in recent years. Home starts peaked in 2021 and 2022 with nearly 100,000 in each year, but have declined since then.

Ontario would have needed to hit an average of 150,000 homes per year since 2021 to hit its target of 1.5 million by 2031.

High interest rates have hit Ontario especially hard, Calandra said. Municipalities have struggled to make land available for development due to a lack of infrastructure needed to service homes, like water and wastewater treatment, he said.

"That is why we then went on the route of the infrastructure in the ground. And I keep talking about it — infrastructure, infrastructure, infrastructure — so that as rates start to come down, which we're seeing now, the serviced land will be available for family-friendly housing," he said.

That 1.5 million target is still reachable, Calandra said.

"I will double down, I'll remove obstacles, we'll reduce costs, and we will meet the target," he said.