No one wants to be stuck in gridlock, inching along a 400-series highway at a crawl.

That’s the future Ontarians can expect if the government doesn’t build Highway 413, according to Premier Doug Ford and his top ministers.

Finance Minister Peter Bethlenfalvy put it this way in a spring speech in downtown Toronto: “Our modelling shows that if we don't build these roads right now, in 10 years, we will be at gridlock in all 400 series.”

“In other words, no going over 40-kilometres an hour — you will be in gridlock if we don't build those roads,” he said, referring to the 413 and the Bradford Bypass.

But bumper-to-bumper gridlock is also the future Ontarians can expect if the government does build Highway 413 and the other new highways on its agenda, according to internal Ministry of Transportation documents obtained by The Trillium through the freedom of information process.

The records show the province knows the 413 won’t end the gridlock, despite government MPPs' frequent suggestions that it will.

The documents include projections of travel times, speed, and congestion in 2041 under various scenarios, including depending on the number of lanes the 413 has and what other transportation projects are completed. They are based on the government’s multimodal travel demand and forecasting tool, the Greater Golden Horseshoe Model.

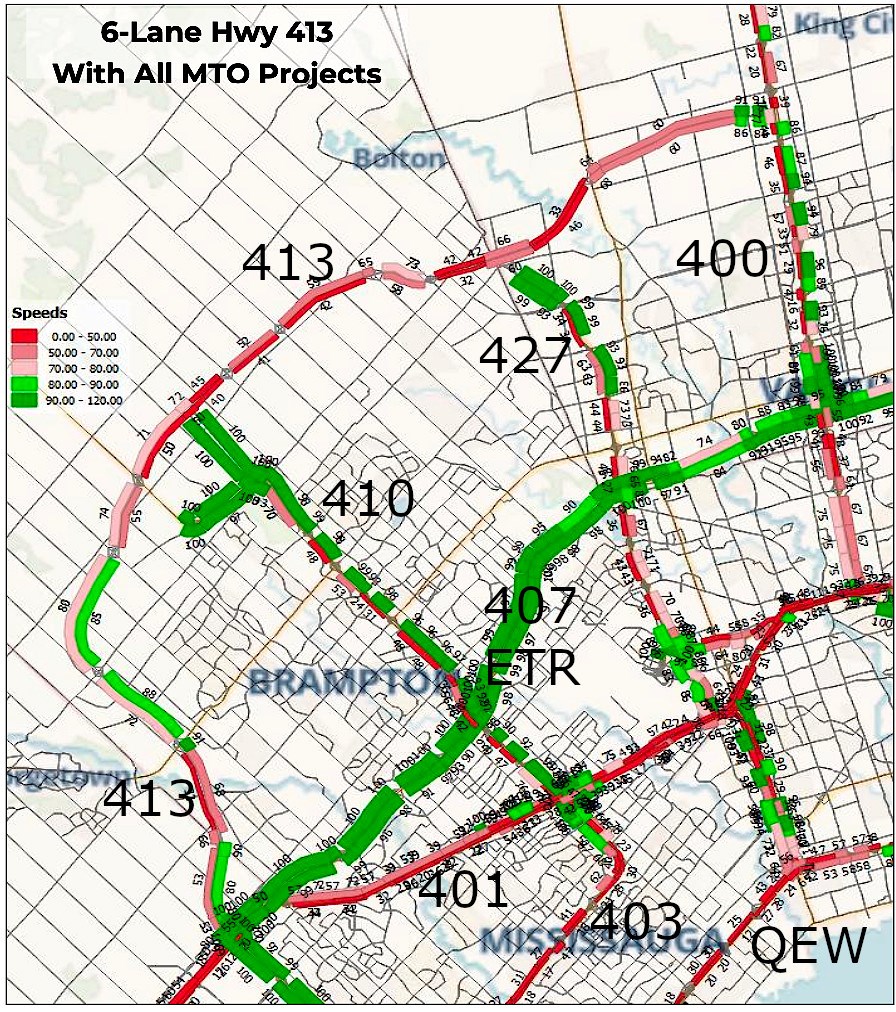

Maps included in the internal documents show incredibly slow typical commute speeds — in the teens, 20s, 30s, and 40s km/hr range on 400-series highways — to and from Toronto during peak travel times in 2041, whether the 413 has four, six, or eight lanes, and whether or not the MTO’s other potential projects are completed.

The government is currently pitching the 413 as a four-to-six-lane highway but documents obtained by The Trillium through a separate freedom of information request show it could grow to 10 lanes by 2041.

A spokesperson for Transportation Minister Prabmeet Sarkaria confirmed that the corridor "will be wide enough to protect for future expansion to 10 lanes, if warranted, in the future."

She did not deny the bleak traffic congestion forecast in the documents. "Without Highway 413 and the governments' other investments in transportation infrastructure, congestion and travel speeds will only be worse," Dakota Brasier said.

When The Trillium showed the records to experts in transportation modelling and planning, they said the documents show not only will 413 fail to end the gridlock, it will also enable the kind of development that makes it worse.

Highway 413 is the most controversial of the Ford government’s planned highway projects because it is expected to have a high environmental impact and, while the government has not released a cost estimate, the auditor general has pegged it at $4 billion and critics expect it to cost more than double that. The highway would stretch from the western edge of Mississauga, where the 407 ETR meets the 401, curve around Brampton, and then reach the 400 at the northern edge of Vaughan.

Other projects include the Bradford Bypass — a link between highways 400 and 404 at Bradford West Gwillimbury — and the widening of sections of the 401 to reduce bottlenecks.

The map below, included in 2022 internal government meeting notes, shows the speed of travel in the morning commute model, with the bright red lines indicating speeds of no more than 50 km/h, including almost all of the 401 heading into Toronto, as well as the 403 and the Queen Elizabeth Way, if the 413 and all other contemplated MTO projects are built. The tolled 407, however, is mostly green, indicating speed of 90 km/hr or higher. The small numbers, some of which are obscured, show projected speeds on individual highway segments. Those that can be read show speeds as low as 12 km/hr, and almost no sections above 50 km/hr. The p.m. commute map is similar but with the lower speeds on the side of the highway heading away from Toronto. (The Trillium added the highway numbers, for ease of comprehension, but the speeds are from the original image.)

Unfortunately, the documents do not include a similar map for a base case in which the 413 is not built. However, the government’s official transportation plan describes what will happen if nothing is done, and it is strikingly similar to what the model predicts will occur with the 413. It warns the segment of Highway 401, between Highway 427 and Highway 404 — “the most travelled, most critical piece of the highway network to the regional economy” — will take twice as long to drive through, with average speeds halved to 30 km/hr by 2051, if no action is taken.

The 413 should not be expected to improve congestion in other parts of the region, according to a leading expert in transportation modelling.

“This highway is, in my view, as much a development play as anything,” said Eric Miller, director of the University of Toronto Transportation Research Institute. “We know this government loves its developers. I can't help but believe that the major impetus for this is to open up these lands to development, which will just make congestion worse, and it’ll be worse than what's being projected here.”

That’s because the development expected around the highway will generate “more traffic, more congestion, more auto dependency,” he said.

Miller doesn’t dispute that the new highway will initially pull some traffic off the 401 — long-distance trips from the west end of the projected highway to the north end, will be quicker with the 413 — but any easing of congestion on the 401 will quickly be filled by commuters from other routes, leaving drivers heading into Toronto no better off.

“Inevitably, the 401 will fill up again,” he said.

Steven Farber, a University of Toronto Professor who studies the social and economic outcomes of transportation and land use decision-making, said one the most striking findings in the government documents is that the 407 is expected to remain underused because the modelling assumes it remains tolled.

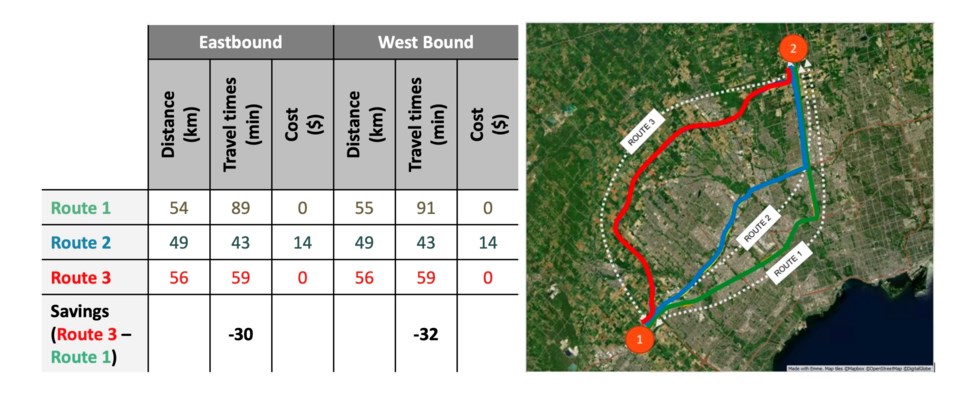

The modelling shows that for drivers heading from one end of the 413 to the other, taking the 407 to the 400 would be 16 minutes faster and seven kilometres shorter.

“To build a new highway that isn't even as good as an empty highway that we have already in existence is bananas,” said Farber. “You could put that on the record, OK? It's nuts. The whole thing is nuts.”

Another document shows that only about five per cent of morning rush-hour drivers will realize the half-hour each-way time savings the government regularly touts.

The premier often cites the figure, including at this year's Good Roads conference, where he promised the 413 will save drivers “up to an hour per day — and five hours per week — on one of the most congested corridors in North America."

Of 22,400 expected 413 users from 6 a.m. to 9 a.m., 1,200 are expected to drive the whole route, saving 30 minutes, an internal technical briefing from 2022 projected. About two in every five 413 users in the morning commute — 8,760 — are expected to travel nearly half the route.

Still, the modelling shows the new highway is expected to become congested — but there's no reason for drivers to use the entire highway if they're heading to or from Toronto or its immediate surroundings, in other words, into "one of the most congested corridors in North America."

Overall, the modelling includes estimates of time savings from 18,000 to 22,000 hours for all drivers in the morning commute as of 2041.

Miller, however, emphasized that a model's outputs are dependent on its inputs — the population and employment area projections in particular.

"My fear is that in this argument for 413, they may well have baked in some projections about population that favour that sort of solution, rather than a more transit-oriented solution," he said.

The modelling also shows that, of the vehicles expected to use the 413, about one in four will be trucks, which further development of warehousing and logistics hubs along the highway could increase. Farber said the logistics industry has been planning expansions near the planned route and would benefit from the new highway — but would also benefit from potentially greater time savings on the 407, if only they’d pay the tolls.

"Those folks are struggling because of traffic, but there's a perfectly empty highway that they should be using in the meantime, and they don't," Farber said.

Earlier this year, the Ontario NDP, backed by a study sponsored by an environmental group opposing the highway, proposed removing the 407 tolls for trucks. Both Miller and Farber said it's worth exploring ideas that rationalize traffic between the 401 and the 407, but Farber stressed the idea poses political challenges.

The 407 ETR is privately run under a lease from the province that isn't set to end until 2098, and subsidizing truck tolls would be an expensive subsidy to the logistics industry, he said. While he suggests tolling the 401, Ford's PCs have explicitly ruled that out, even passing legislation that seeks to force any future highway toll to be subject to a referendum.

Brasier, the spokesperson for the transportation minister, said modelling showed the 407 would be at or above capacity by 2031 without the 413, referring to previous modelling that was done for the highway's environmental assessment over a decade ago.

"If we simply divert gridlock from one highway to another and don’t build any new capacity, we will find ourselves with the same problem, but worse 10 years down the road," she wrote.

The solutions, according to the experts, aren't easy.

"There is no real solution to traffic except to take cars off the road," said Farber. "You can't build yourself out of traffic by building more road infrastructure. It doesn't work anywhere in the world, and it won't work here. So the only real solution is to create viable alternatives, and we don't have a lot of viable alternatives for most people, and for most trips that get made in this region, there aren't a lot of viable alternatives to driving."

Miller agreed.

"Congestion is not just a traffic engineering problem," Miller said, adding that he teaches a graduate-level course in what that means. "It's much more a land-use and urban form problem, we have built an urban region — and this is true through most of North America — that is predicated on using the car and does not support good transit, and then we wonder why we have congestion."

It's not easy to change the form of a region that's been built the same way for the last 80 years, he said.

"To me, this is the frustrating thing about the 413. It's the same 1950s, 1960s mentality of how to build a region: you will have a highway, and that's going to solve our problem," he said. "We have 60 years of experience saying that that doesn't work and yet this government is locked into that mentality."

In her statement on behalf of the transportation minister, Brasier stressed the time savings shown by the modelling and added that the government is building "the largest transit expansion in North American history" as well as highways.

"We know that as the population increases, congestion is only going to get worse, and we need to build infrastructure now to plan for the future and ensure hard-working Ontarians can get where they need to go each and every day," she said.

"The reality is, Ontario’s population is rapidly growing, and after decades of inaction by the previous government, our infrastructure needs to keep up."

The provincial government won a victory in its 413 campaign when the federal government dropped its environmental assessment of Highway 413 following a Supreme Court ruling that parts of the federal Impact Assessment Act were unconstitutional. The two governments have formed a Highway 413 working group to handle federal processes concerning the Fisheries Act, the Migratory Birds Convention Act, and the Species at Risk Act. Environmental Defence, a staunch campaigner against the highway, has been calling on the federal government to redesignate the highway for an impact assessment.